Tracing: Amerika-Gedenkbibliothek (1954) (English)

After the end of the Berlin Blockade, the Americans wanted to build a memorial to the Airlift and the successful cooperation between West Berlin and the United States. West Berlin's mayor Ernst Reuter suggested that this memorial could be a library (cf. Breitenbach 1954, 281), since a major challenge for West Berlin was the »loss« of books to the East after the city was divided (Humboldt University, the Berlin City Library, and the Berlin State Library were all in the East). So a provisional library was set up in Dahlem. McCloy and the American government provided 4.4 million DM for the building and the acquisition of books as part of the Marshall Plan. Initially, Reuter conceived the new library as an academic library for the newly founded Free University (FU) in Dahlem, but he wanted to build the library in Kreuzberg. Not only had the district been severely damaged during the war, but it was also centrally located: In anticipation of the city's eventual reunification, this new library would be a central point of the city. However, in a divided city, Kreuzberg was also close to the Wall and the border, and thus a new library could show the »successes of the West« to the East – after all, it was the beginning of the Cold War. The FU, however, was unhappy with this, from a Dahlem perspective, remote location. When the Ford Foundation agreed to finance the construction of a new lecture hall and library for the FU – which was to become the Henry-Ford-Bau – the newly conceived library in Kreuzberg could be established not as an academic, but as a public library.

The choice of location was, thus, symbolic, as the building was to »stand as a widely visible monument to the freely developing spirit in the immediate vicinity of the eastern sector, as well as a witness to the belief in the reunification that would sooner or later take place here in the heart of the old city« (Moser 1954, translated from German). Indeed, from the top floor, which was not open to the public, one could see the border: »Checkpoint Charlie« interrupted the busy street of Friedrichstraße, at the end of which the library was conceived as an »opening gesture«.

In the 18th century, the property had served as a garden with »exotic plants and foreign animals« and was called »New America«. Even after the garden disappeared in the 19th century, the name »New America« remained on old maps as a »spiritus loci« – showing how Colonial ideas of the Americas had been inscribed into the site long before.

Flexibility in space and time was the main architectural concept. US-americans as donors and the Berliners as clients agreed on the public character of the building. Not only should everyone have free access, but it was thought that the building should also take into account future »changes in social structure, in education and the concept of education, and in the position and significance of scientific life in the present« (Moser 1954, translated from German).

After an »ideas competition« with 194 architects from West Berlin and West Germany, no design was chosen as the winning proposal, as all designs lacked some elements. This was the largest public library project in Germany at the time, and there was no design experience of such endeavor in Germany. Two US-american architects were chosen to assist a selected group of four German architects: Gerhardt Jobst, Willi Kreter, Hartmut Wille, and Fritz Bornemann were assisted by Francis Kelly (who built the great public library in Brooklyn with Alfred Morton Gitters and others) and by the assistant director of the public library in Detroit, Charles M. Mohrhardt (cf. Moser 1954). The new library was sponsored by the Library of Congress in Washington, which sent Dr. Edgar Breitenbach as a consultant, as well as other staff members, to help establish the new library. Later, in return, German staff members of the new library were sent to the United States for studying purposes (cf. Moser 1954). This promoted knowledge exchange has left its marks in the library’s collection: The Library of Congress was the first donor to the collection of the new American Memorial Library.

The main goal of the spatial layout was »to make access as convenient and clear as possible for the public« and »to allow the technical organization of the library great freedom of movement in the use of the entire facility through the sparing use of load-bearing walls and supports« (Moser 1954, translated from German). The cornerstone was laid on June 29, 1952. The new library was to be a symbol not only of »superior Western democracy«, but also of a »friendship between the American and German peoples«, as declared by the then U.S. Secretary of State. Fritz Moser, the first director of the library declared that the institution »seeks to do its part to build a bridge of understanding from person to person and people to people« (Moser 1954, translated from German).

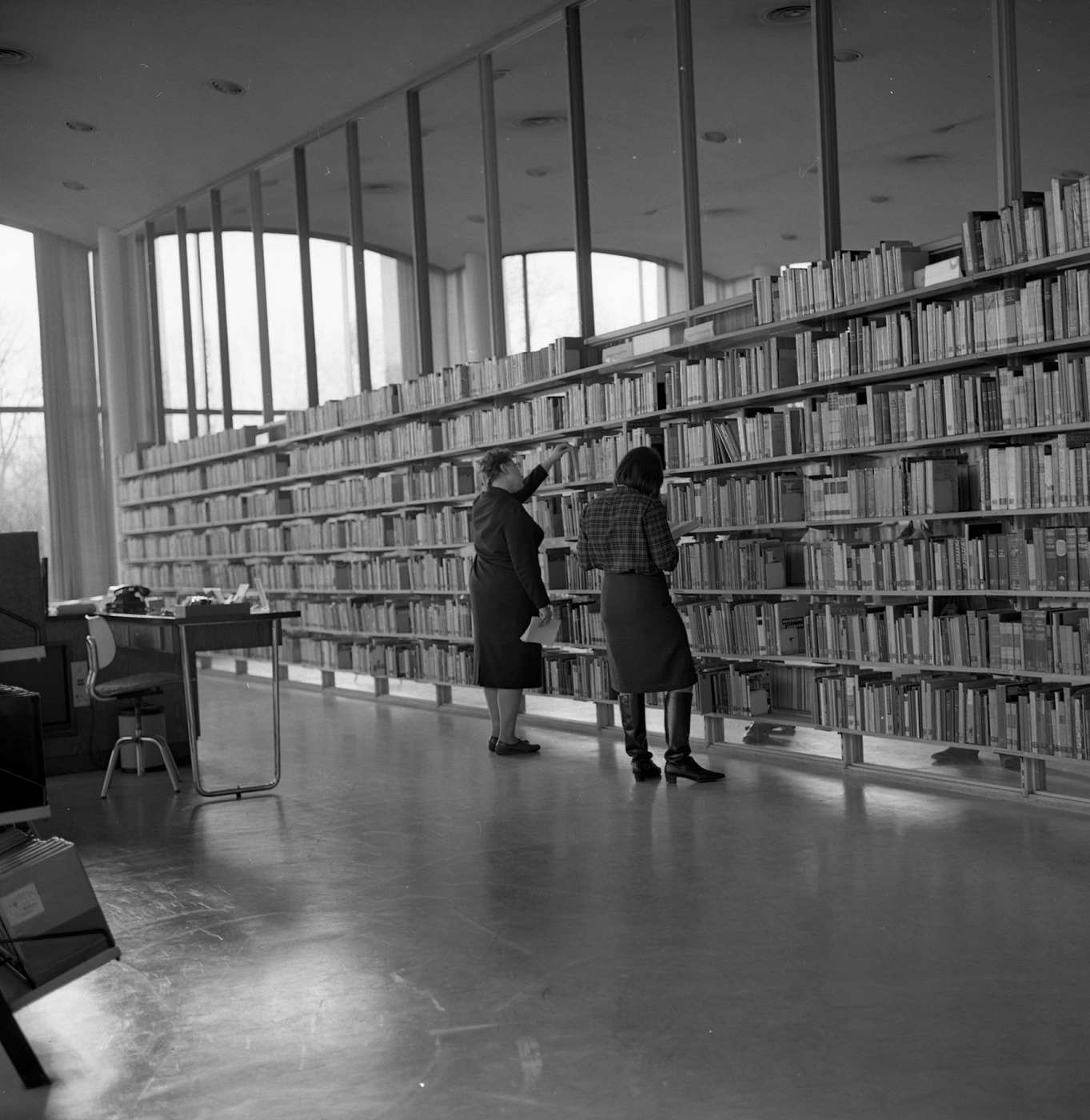

While the building was under construction, books had to be acquired and a classification system developed. Acquisitions were made on the basis of »utility value« rather than »optimal completeness«: This public library should serve its users in their daily lives and not primarily serve a collector’s value. Thus, the special feature of the new library was the free lending system (Freihandausleihe, see Amerika Haus), which included not only fiction but also academic books. Both this open lending system and the combination of nonfiction and fiction were novel for a public library in Germany (cf. Breitenbach 1954, 283).

The large book depot [Magazin] allowed for an even greater variety of available books. The location of this depot in the basement allowed for quick delivery of requested books to the reading room. From the beginning, it was important that this library not only collects and provides media, but also creates a space and opportunity for public discourse and exchange by organizing lectures, etc., in the attached auditorium.

The ground floor was and is reserved to the public. Here the theme of accessibility and flexibility has been inscribed into the space: The bookshelves are located on the ground floor and are therefore easily accessible. No stairs hinder intellectual access – yet, the main bathroom remains located in the cellar. Together with the glass doors, the book shelves form the only divisions and create different zones between more quiet and more active spaces. Visitors enter the building from the north and find themselves in a brightly lit (daylight) entrance situation due to the large window front. To the right, a large quote by Thomas Jefferson is inscribed into the wall, and serves as a reminder to the grand ideals of the library’s founders. At the back, the building opens to the south, towards the garden, which is articulated by the slightly sloping roof that rises to the south for better light incidence and cantilevers out to create built-in sun protection.

Workshops, administration, and storage are »hidden« in the six-story building at the heart of the complex, whose weight is not to be felt when circulating freely through the ground floor spaces. The tall building with its stern grid facade serves as a marker in the urban context, situating the library in the heart of Kreuzberg.

Text by Hannah Strothmann

Bibliography:

Moser, Fritz (1954): Amerika-Gedenkbibliothek, Berliner Zentralbibliothek: zur Eröffnung am 17. September 1954, Berlin.

Moser, Fritz (1955): »Die Berliner Gedenkbibliothek«, in: Bauwelt 8, S. 141-149.

Breitenbach, Egar (1954): »The American Memorial Library in Berlin, Its Aims and Organization«, in: Libri 4/4, S. 281–292.